Understanding clinical research is essential for evaluating health claims. This guide provides a framework for reading and critically evaluating clinical studies.

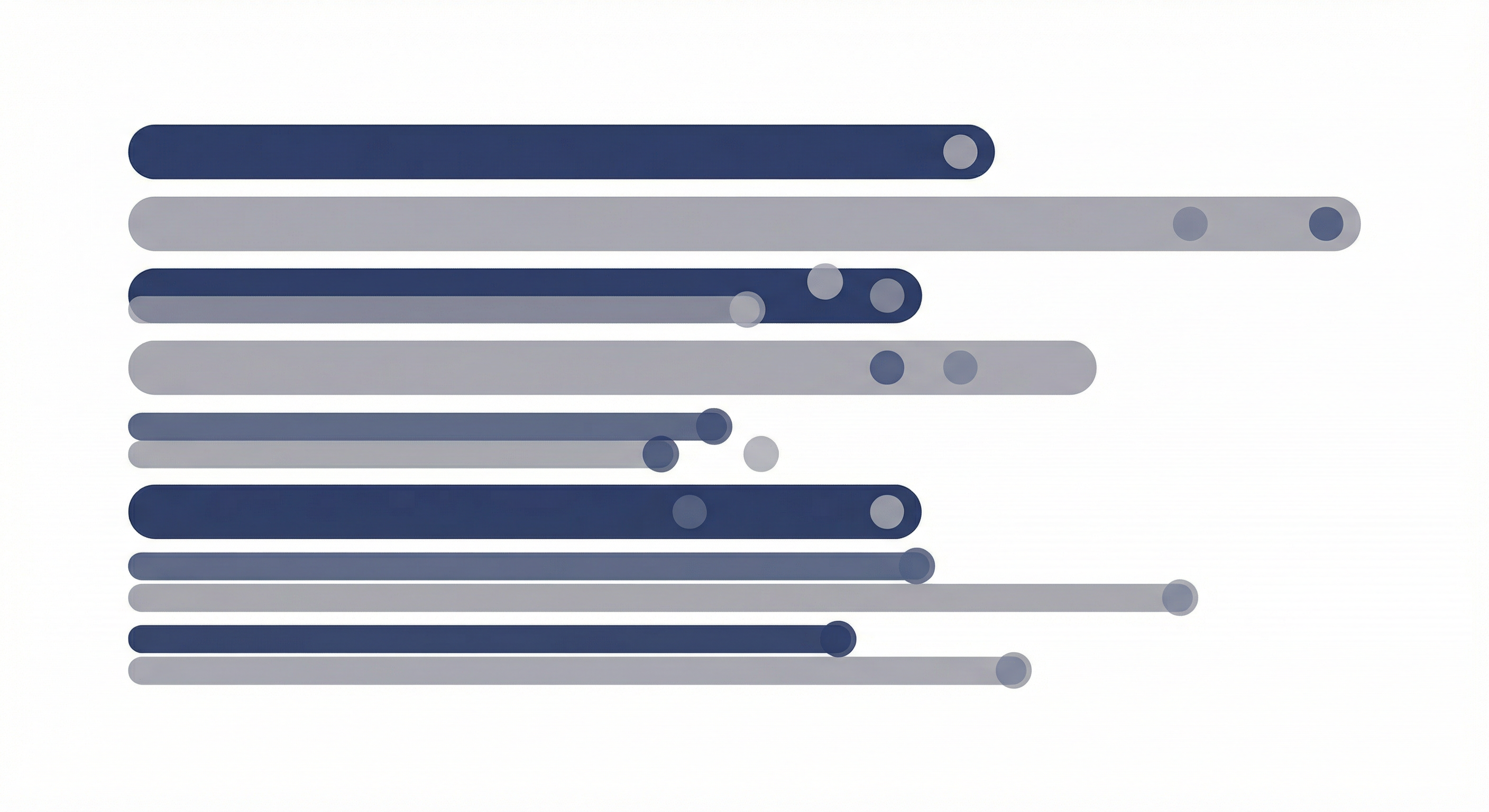

The Hierarchy of Evidence

Not all research carries equal weight. Studies are ranked by their ability to minimize bias:

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: Aggregate and analyze multiple studies on the same question

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs): Participants are randomly assigned to treatment or control groups

- Cohort studies: Groups are followed over time to see who develops outcomes

- Case-control studies: Compare people with an outcome to similar people without

- Case series and case reports: Descriptions of individual patients or small groups

- Expert opinion: Opinions without systematic critical appraisal

Understanding Study Design

Randomized Controlled Trials

RCTs are considered the gold standard for testing interventions. Key features include:

- Randomization: Participants are randomly assigned to groups, reducing selection bias

- Control group: A comparison group receives placebo or standard care

- Blinding: Participants, researchers, or both are unaware of group assignments

RCT limitations include expense, ethical constraints, and limited ability to study long-term outcomes or rare events.

Observational Studies

Observational studies do not involve researcher intervention. They can identify associations but cannot establish causation:

- Cohort studies: Follow groups forward in time

- Case-control studies: Look backward from outcomes to exposures

- Cross-sectional studies: Measure exposure and outcome at one point in time

Critical Appraisal Questions

When reading a study, consider these questions:

About the Study Population

- Who was included and excluded?

- How many participants were enrolled?

- Are participants similar to the population you care about?

- How many dropped out, and why?

About the Intervention

- What exactly was the intervention (dose, duration, delivery)?

- What did the control group receive?

- Could participants tell which group they were in?

About the Outcomes

- What outcomes were measured?

- Were outcomes objective or subjective?

- Who assessed the outcomes? Were they blinded?

- How long were participants followed?

Understanding Statistical Results

P-Values and Statistical Significance

A p-value indicates the probability that the observed result would occur by chance if there were no real effect. By convention, p < 0.05 is considered "statistically significant."

However, statistical significance has important limitations:

- Statistical significance does not mean clinical significance—a result can be statistically significant but too small to matter clinically

- P-values do not indicate effect size or importance

- Multiple comparisons increase the chance of false positives

Confidence Intervals

Confidence intervals provide a range of plausible values for the true effect. A 95% confidence interval means that if the study were repeated many times, 95% of the intervals would contain the true value.

Narrow confidence intervals indicate more precise estimates; wide intervals indicate greater uncertainty.

Absolute vs. Relative Risk

Relative risk reductions can be misleading without context:

- Example: A treatment that reduces risk from 2% to 1% offers a 50% relative risk reduction but only a 1% absolute risk reduction

- Always look for absolute numbers when evaluating claimed benefits

Common Biases and Limitations

- Selection bias: Participants differ systematically from the target population

- Attrition bias: Participants who drop out differ from those who remain

- Publication bias: Positive results are more likely to be published than negative ones

- Funding bias: Industry-funded studies may be more likely to report favorable results

- Confounding: Other factors may explain the association between exposure and outcome

Red Flags in Research Reporting

Be cautious when you see:

- Claims based on a single study

- Animal or cell studies presented as applicable to humans

- Failure to disclose funding sources or conflicts of interest

- Absence of control groups

- Very small sample sizes for the claims being made

- Only relative (not absolute) risk reported

- Outcomes that were not pre-specified

Summary

Reading clinical research critically requires understanding study design, recognizing limitations, and interpreting statistics appropriately. No single study provides definitive answers—conclusions are strongest when supported by multiple, well-designed studies with consistent findings.

References & Further Reading

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence. University of Oxford.

- NIH National Library of Medicine. Health Economics Information Resources Glossary. NLM.

- CONSORT Group. CONSORT Statement for Reporting Randomized Trials.

- Cochrane Training. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.